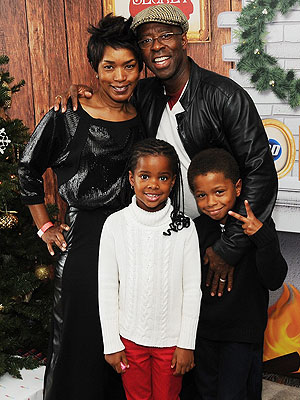

Angelos Tzortzinis for The New York Times

Ms. Alevridou's support of Voukefalas has caused an uproar.

LARISSA, Greece — Her soccer club looked ragged. Strikers jumped up for headers only to miss the ball entirely. Players tumbled over one another, shouting out accusations that they had been fouled.

But in the bleachers, Soula Alevridou, or “Madam Soula,” as she is known in these parts, watched intently, a petite woman in a man’s tie smoking ultra thin cigarettes.

“Keep in mind that the home team is very good,” she said, explaining the difficulties that her team, Voukefalas, was having.

Madam Soula, a former prostitute and now, at the age of 67, the owner of two luxury brothels here in Larissa, stepped in this fall to sponsor Voukefalas, a small amateur soccer team that like many others in Greece was having trouble coming up with the cash for uniforms, equipment and playing field fees.

She considers her support a natural thing to do, maybe even a patriotic gesture, because her debt-mired country is in so much trouble that many of life’s extras, like amateur sports, are becoming out of reach.

“A friend asked and I said, ‘I am here,’ ” she said.

But local officials in this once-rich farming area are hardly thanking her for her efforts. In fact, her gift of about $1,300 so far, in part to buy bubble-gum pink training outfits — has caused something of an uproar as officials debate the appropriateness of having a brothel owner step in, even if it is to make up for a bankrupt state and an economy that leaves few businesses with the cash to help young men play sports.

In an interview, Larissa’s mayor, Konstantinos Tzanakoulis, pointedly ignored questions about the matter. And the Larissa soccer league recently informed Voukefalas that team equipment bearing the name of Madam Soula’s brothels — Villa Erotica and House of the Era — would not be tolerated, though brothels are legal in Greece. The league warned that any infraction, not only in games but also during “training, warm-ups, interviews and friendly matches,” would land the team in disciplinary hearings for “defamation of the sport.”

The team’s president, Ioannis Batziolas, 29, a backup goalie, calls the league’s decision hypocritical, and points out that Greece’s professional soccer championship is sponsored by the state-owned lottery and betting company OPAP, which is soon to be privatized. “What is the better idea to promote?” he asks. “Gambling or sex?”

For a time, this city of 200,000 at the foot of Mount Olympus seemed to be weathering the Greek crisis better than most. But the years of recession are piling up and most businesses are suffering. Unemployment is over 20 percent, higher among young people.

Madam Soula said her business had been hurt, too. But not that much. Customers sometimes even fly in from Britain, she said, drawn by Internet ads.

Mr. Batziolas said he looked everywhere for team sponsors, but found nothing until Madam Soula came forward. His own travel agency, L.A. Travel, provided most of the money last year. But it just could not afford to any longer, he said. On top of that, he has not seen the government’s share of support in several years. “They owe me thousands,” he said.

Mr. Tzanakoulis, who has been mayor here for more than a decade, says that the municipality is continuing to support sports, but that the central government has not been delivering, which leaves a great need.

“Sports are important for young men,” he said. “It is a good activity that keeps them out of trouble.” But that is all he will say on the subject of Voukefalas (the team is named after Alexander the Great’s horse) and the team’s new sponsor.

Voukefalas is not the only team to have been creative in looking for sponsors. Another soccer team got a funeral home to act as a sponsor and for a while wore black T-shirts with white crosses. But league officials did not like that either.

Madam Soula tries to shrug off the hullabaloo over her sponsorship. “Do they have anyone else to give them the money?” she asks.